CHRONIC PROGRESSIVE LYMPHOEDEMA (CPL)

CPL is a condition which we are seeing with increasing frequency in our ‘hairy’ population – draft breeds, cobs and certain natives. It was only relatively recently (2003) recognised as a specific, stand-alone condition, and it is still not fully understood, but here is what we know so far.

- As the name suggests, this is a long term (‘chronic’) condition which progresses over time, resulting in build-up of lymphatic fluid within the tissues (‘lymphoedema’) of the lower limbs.

- Longstanding lymphoedema results in inflammation, tissue fibrosis and changes in the elastin fibres in the affected areas, resulting in ongoing reduced ability for the lymphatic fluids to drain from these areas – so you get a vicious cycle of fluid build-up.

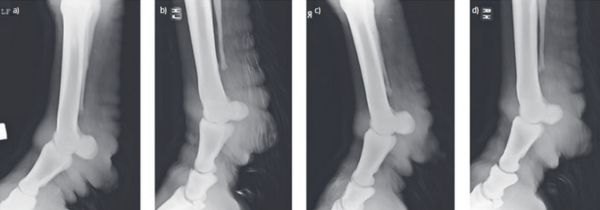

- Affected horses develop ‘rolls’ or ‘nodules’ of thickened skin – in more severely affected cases these can be seen despite the feathering, but in milder/early stage cases they might not be obvious, and may only be picked up by palpation of the limbs.

- There will also be increased exudate (the ooze that comes from the skin), crusts, hyperkeratosis, and thickening of the skin layers.

- Cases range from only mildly affected (where you may need to get ‘hands on’ to diagnose by palpation) to severely affected (thickened rolls around the whole circumference of the limb, potentially extending further up the limb to the hocks or knees).

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, CPL is a lifelong condition for which there is no cure; instead, management is focused around four areas, to try and slow down the progression and reduce symptoms.

- Lymphatic drainage – movement is really important! Studies show that horses who have less movement are more likely to be severely affected than those used for riding/working. Muscular activity acts as a pump for the lymphatic vessels. There are also massage techniques that can be used, and in some cases compressive bandaging has been used – but the latter is tricky to perform correctly, and the risk of bandage sores is high.

- Skin hygiene – secondary bacterial skin infections are common in these cases, due to the increased skin exudate and thickening. Clipping is strongly advised to allow access to the skin, and regular cleaning/washing of the limbs in suitable shampoos/solutions, and application of topical antibacterials. Also – good stable hygiene is important!

- Ectoparasite control – whilst feather mites are not the sole cause of CPL, they can make things worse by causing further irritation and inflammation. In severe cases where there are thick crusts, topical mite treatments applied after cleaning of the limbs may be recommended over injectable treatment, as the mites may be ‘hidden’ within the thick crusts and not accessible by an injected treatment. Maggots (‘flystrike’) are also possible in some cases.

- Diet – higher starch/sugar diets are linked to higher insulin levels, and in turn higher levels of inflammatory cytokines within the blood stream – this can promote inflammation within the lower limbs. Therefore, a low sugar diet is recommended in these horses, and weight loss where appropriate.

Some horses with CPL may benefit from long term pain relief, to promote movement and reduce inflammation in the affected areas.

It is believed that there is likely to be a genetic link with CPL, which is why some breeds are much more likely to be affected than others, and why some individual horses will suffer from CPL and others not, despite the same management. Unfortunately, this link is not proven yet but is an ongoing area of research. We would recommend careful consideration before breeding from a horse affected with CPL however, due to this possibility.