Grass Sickness is a disease of horses, ponies and donkeys in which there is damage to parts of the nervous system which control involuntary functions, producing the main symptom of gut paralysis.

Also known as Equine Grass Sickness (EGS) the cause is unknown but the nature of the damage to the nervous system suggests that a type of toxin is involved – potentially botulism neurotoxin acquired from soil.

The toxin may also affect nerves supplying other body systems resulting in other signs of EGS such as droopy eyelids, inability to swallow & muscle tremors to name but a few.

Three forms of the disease have been reported: the acute, subacute and chronic forms. The form a patient succumbs to depends on the extent of nerve damage.

Horses affected by the acute form of the disease present showing signs of colic often indistinguishable from other forms of colic meaning that it may be suspected that the patient has a twisted gut or other form of surgical colic.

As a result, such patients often undergo colic surgery and the diagnosis of EGS is often made presumptively on the surgery table. This form of the disease is 100% fatal.

In horses with subacute or chronic EGS, the time course of the disease is more gradual and these patients may present with a high heart rate, mild episodes of colic, a tucked up appearance, an inability to swallow, drooling saliva, droopy eyelids, muscle tremors and patchy sweating. This form of the disease is also fatal.

Horses with the chronic EGS may survive but require intensive management to maintain hydration and nutritional requirements. The likelihood of survival depends on the extent of nerve damage.

The only way to definitively diagnose EGS is to examine an intestinal biopsy. Surgery is required to obtain a biopsy. Therefore, horses are frequently diagnosed based on the presence of compatible clinical signs.

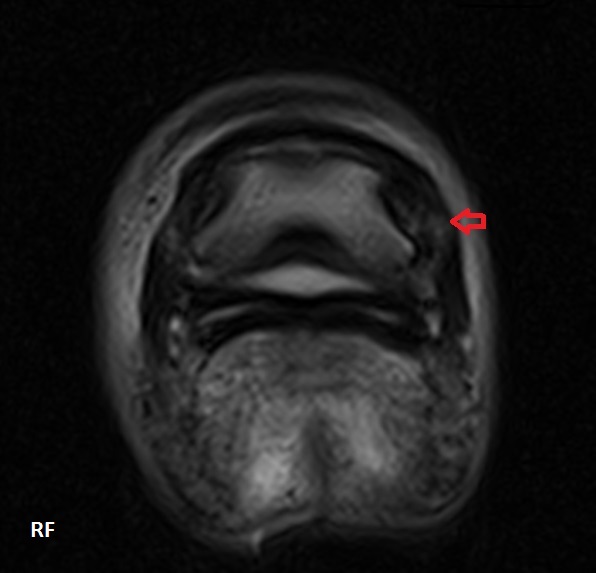

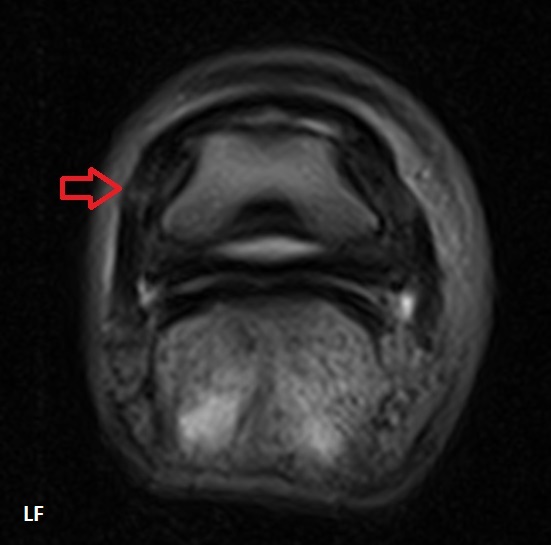

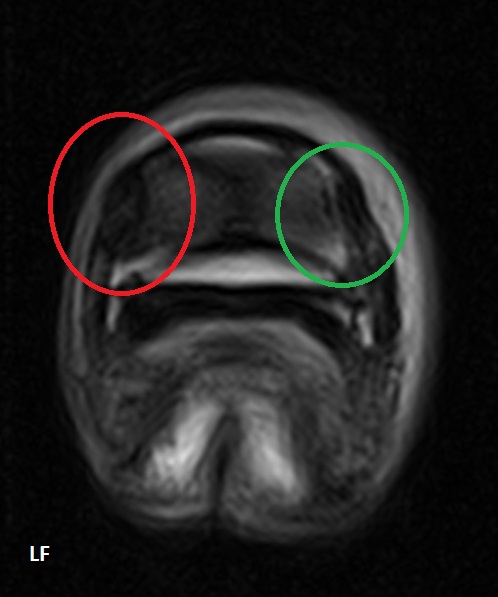

Vets often perform an eye drop test known as a phenylephrine test. When these drops are applied to one of the patient’s eyes the droopy eyelid appearance improves. Other conditions may also cause droopy eyelids so this test is by no means perfect.

Horses at risk of succumbing to EGS include any horse at grass but the condition is most commonly seen in young animals aged between 2 & 7 years.

Cases have been reported throughout the year but occur most frequently in late spring/early summer. Overweight horses are also at increased risk. Other reported risk factors include recent soil disturbances, overuse of ivermectin based wormers, a recent change in pasture & being at grass 24/7.

Prevention is based on avoiding changes in management, especially in youngstock, at the ‘at risk’ time of year. Soil disturbances should also be kept to a minimum. Ideally, horses should be stabled for at least part of the day and offered hay or haylage. Furthermore, overuse of ivermectin based wormers should be avoided and ideally, a wormer containing an alternative drug should be used prior to turn out. Co-grazing with sheep or cattle may also be protective.

When a case has been diagnosed at a property,it is of paramount importance to stay calm and to avoid any sudden changes in management. In our opinion, in-contact horses should not be moved field as moving pasture is itself a risk factor for

EGS. Furthermore, fields within a 10km radius are theoretically ‘at risk.’ Co-grazing with a patient that has succumbed to EGS may itself be protective suggesting an acquired immunity. We would; however, recommend that young horses are kept off an affected field during future grazing seasons.

A vaccine trial is currently underway which, if licensed, will hopefully provide us with an effective means of preventing EGS in the future.