Oakhill Equine Vets is a 12-vet dedicated, equine-only team. We are extremely lucky at Oakhill to have a highly qualified equine veterinary team with 111 years experience between them! Guy and Rosie are both European and RCVS recognised specialists in Equine surgery and lameness. We also have two vets with RCVS advanced practitioner status, Jess and Leona. Leona has a certificate in Internal Medicine and the rest of our outstanding team are studying towards a further 7 certificate qualifications between them!

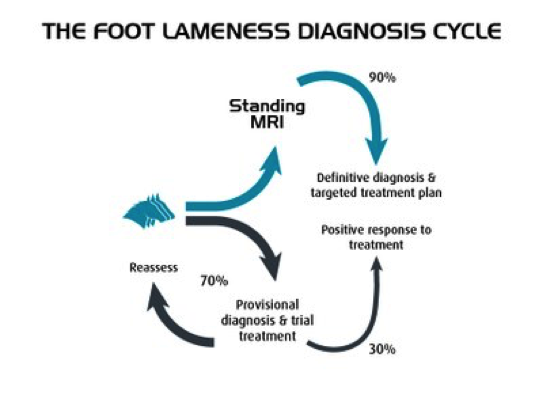

Oakhill has a fully-equipped surgical facility including state of the art arthroscopy equipment, anaesthesia recovery box and advanced anaesthetic monitoring equipment. We host an array of specialist equipment including MRI, digital radiography, multiple endoscopes and a dental oral endoscope, in order to achieve the highest possible standards of care for your horse.

Due to the depth of team experience and the quality of our equipment at Oakhill, we offer an extensive referral service to other practices across Lancashire, Cumbria and Cheshire. We have two vets on call 24/7 to ensure that we can attend any emergency promptly within our practice area.

We are dedicated to providing a 5* level of service to you and your horse. Our team is also focused on providing education to clients regarding their horse’s care via phone advice, social media, informative newsletters and client talks. No matter what the problem is, we are here to offer a professional and compassionate service to our valued clients.

Positioning

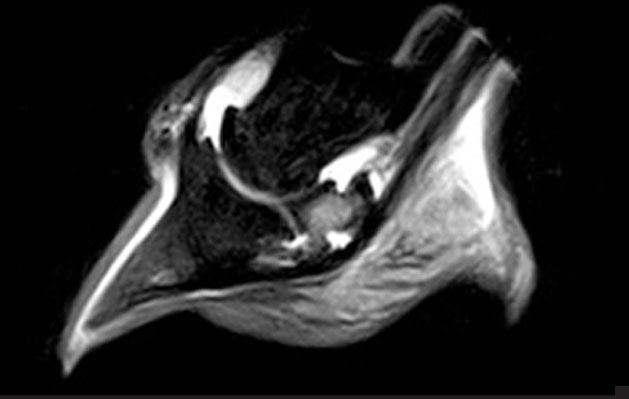

Positioning The scan takes around 2 – 4 hours, producing around 300-500 images at multiple angles of the limb or hoof, highlighting different types of tissue and pathology.

The scan takes around 2 – 4 hours, producing around 300-500 images at multiple angles of the limb or hoof, highlighting different types of tissue and pathology.

Is it the same as a human MRI scanner?

Is it the same as a human MRI scanner?